date

stringlengths 10

10

| nb_tokens

int64 60

629k

| text_size

int64 234

1.02M

| content

stringlengths 234

1.02M

|

|---|---|---|---|

2018/02/24

| 1,013

| 4,385

|

<issue_start>username_0: I work as a full-time employee in industry. Recently, I've been invited to present at a conference in an area not closely related to my degree. My employer approved me being absent for two-three hours and I accepted the conference invitation.

However, I'm not sure how will this look in the eyes of the conference attendees and other presenters since I will have to leave immediately after my 20 minutes talk. Therefore, I will miss their talks.

Is there an etiquette regarding this? Should someone accept a presentation on a conference if they won't be able to be present for the whole duration?<issue_comment>username_1: No one can force you to attend the whole conference, but usually the purpose of conferences is to spread new ideas, discuss them and make connections.

You can certainly accept the invitation, deliver your presentation and disappear soon afterward. It's certainly not unheard of. Your presentation might be useful to others anyway, but you will miss part of the purpose of going to conferences.

Upvotes: 7 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_2: It's certainly not viewed as odd to leave a conference straight after your presentation, plenty of people do it if they are super busy. However you will unfortunately have to skip the value of hearing other presentations, feedback on your own work and of course networking.

Upvotes: 4 <issue_comment>username_3: >

> Is there an etiquette regarding this? Should someone accept a presentation on a conference if they won't be able to be present for the whole duration?

>

>

>

There aren’t really any universally agreed-upon rules for such things, but as a general rule:

1. If the conference organizers are paying any expenses for your attendance (such as travel or accommodation), it is considered good manners to be present for at least a good chunk of the conference other than your own talk.

2. If the organizers are not paying your expenses, I don’t think they have either a moral claim or much of an expectation that you do anything other than show up and deliver the talk they invited you to deliver.

If you are in doubt about what the organizers are expecting from you, it is perfectly acceptable to let them know about your constraints and ask them if it’s okay to accept the invitation even though you won’t be able to stay after your talk. If it bothers them, I‘m sure they will have no trouble telling you.

Upvotes: 6 <issue_comment>username_4: One practical issue not addressed in the other answers is the size of the conference. If this is a large conference with multiple concurrent sessions and hundreds of attendees, there will be so much moving about between talks that no one will even notice when you leave. Even if someone is actively seeking you out for a one-on-one discussion they may simply assume they missed you in the throng.

On the other hand, if all talks follow one another in a single location and there are a few dozen attendees, you are more likely to be missed if you leave early. In that case, I doubt many would regard it as rude, but it's certainly possible that other attendees might feel disappointed if they had been hoping to have a discussion with you.

One practical tip: (particularly) if you are forced to leave early, make sure that your contact details are prominently included in your talk and easy to find via your company's website or on social media. Then if people would like to follow up anything from your talk they have the means to do so even if they can't speak to you at the conference.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_5: Don't leave the conference right after presenting the paper, and don't arrive right before you need to present it. At least come for the day.

Some answers tell you "oh, there's no obligation if they're not paying your expenses etc." ... well, nobody's going to hang you for it, but still: **It's a conference. Attend the conference. Mingle. Talk to people.** It's important for the scientific community and probably beneficial for you as well. You won't regret it.

What about your employer, then? Well, tell him you are expected to show up for the full day, and you had made a mistake only asking for part of the day off. And if you're working someplace which can't give you a day off to attend a scientific conference - well, you have bigger problems than leaving a session early.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/24

| 972

| 4,139

|

<issue_start>username_0: I currently study for my B.Sc. in Media IT. I easily could finish a second Bachelor if I do one more semester. I want to do master's degree in Media IT afterwards.

I'm already 23 and in the third semester, since I finished an apprenticeship as a software developer before. Is it useful to start my master's with 26 and probably finish it when I'm ~28?<issue_comment>username_1: No one can force you to attend the whole conference, but usually the purpose of conferences is to spread new ideas, discuss them and make connections.

You can certainly accept the invitation, deliver your presentation and disappear soon afterward. It's certainly not unheard of. Your presentation might be useful to others anyway, but you will miss part of the purpose of going to conferences.

Upvotes: 7 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_2: It's certainly not viewed as odd to leave a conference straight after your presentation, plenty of people do it if they are super busy. However you will unfortunately have to skip the value of hearing other presentations, feedback on your own work and of course networking.

Upvotes: 4 <issue_comment>username_3: >

> Is there an etiquette regarding this? Should someone accept a presentation on a conference if they won't be able to be present for the whole duration?

>

>

>

There aren’t really any universally agreed-upon rules for such things, but as a general rule:

1. If the conference organizers are paying any expenses for your attendance (such as travel or accommodation), it is considered good manners to be present for at least a good chunk of the conference other than your own talk.

2. If the organizers are not paying your expenses, I don’t think they have either a moral claim or much of an expectation that you do anything other than show up and deliver the talk they invited you to deliver.

If you are in doubt about what the organizers are expecting from you, it is perfectly acceptable to let them know about your constraints and ask them if it’s okay to accept the invitation even though you won’t be able to stay after your talk. If it bothers them, I‘m sure they will have no trouble telling you.

Upvotes: 6 <issue_comment>username_4: One practical issue not addressed in the other answers is the size of the conference. If this is a large conference with multiple concurrent sessions and hundreds of attendees, there will be so much moving about between talks that no one will even notice when you leave. Even if someone is actively seeking you out for a one-on-one discussion they may simply assume they missed you in the throng.

On the other hand, if all talks follow one another in a single location and there are a few dozen attendees, you are more likely to be missed if you leave early. In that case, I doubt many would regard it as rude, but it's certainly possible that other attendees might feel disappointed if they had been hoping to have a discussion with you.

One practical tip: (particularly) if you are forced to leave early, make sure that your contact details are prominently included in your talk and easy to find via your company's website or on social media. Then if people would like to follow up anything from your talk they have the means to do so even if they can't speak to you at the conference.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_5: Don't leave the conference right after presenting the paper, and don't arrive right before you need to present it. At least come for the day.

Some answers tell you "oh, there's no obligation if they're not paying your expenses etc." ... well, nobody's going to hang you for it, but still: **It's a conference. Attend the conference. Mingle. Talk to people.** It's important for the scientific community and probably beneficial for you as well. You won't regret it.

What about your employer, then? Well, tell him you are expected to show up for the full day, and you had made a mistake only asking for part of the day off. And if you're working someplace which can't give you a day off to attend a scientific conference - well, you have bigger problems than leaving a session early.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/25

| 415

| 1,793

|

<issue_start>username_0: I submitted an assignment 1 day late. Should I email the professor to explain my situation? He has a pretty loose policy on deadlines but we should definitely submit the assignment before the answer is posted.

I dropped the assignment in his mailbox so if he does not check on Sunday and posts the answer keys on the same day, he might be suspicious of me submitting the assignment after the answer key is posted, which is way less acceptable.<issue_comment>username_1: Tell him, he may or may not accept your submission, but if he wants to accept it and needs proof that it was before the answers came out then telling him provides that.

Don't provide a 16 page opera about why it was late, an apology, a (short) reason : medical etc and close.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_2: By all means, tell your professor why the assignment was late. Your professor may interpret your silence as a sign that you either don't care that your work is late or that you have no reason to explain your lateness. Most teachers, even if they have a lenient policy on late assignments, expect assignments to be turned in on the due date, and if your assignment is late, your professor may interpret the lateness as a sign of disrespect, which, in many circumstances, it is.

If you have an acceptable reason for your lateness, your professor will at least see your explanation as a polite attempt to justify yourself. If you have no good reason, then couch your explanation in something like this: "Although I don't have a good excuse for turning my assignment in late, I do have a reason to explain my tardiness. . . ." And then briefly explain the cause of the lateness.

In almost all cases, more, rather than less, communication with your teachers is a good idea.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/25

| 855

| 3,496

|

<issue_start>username_0: I'm a student in India. My music teacher was kicked out of the school about 1 month ago due to sexual misconduct.

Today, he messaged me on Instagram with a fake ID and started talking nastily to me so I blocked him. He again messaged me with a new ID and asked for pictures and so on. I had to block him 3 more times.

He again messaged with a new ID of a girl.

I gullibly replyed to the message but again he asked for pictures and some sexual chats so I blocked him once more.

This is not ending. He was my teacher and this attitude of his is not good.

What should I do to stop him doing this?

And to prevent many girls from getting affected by this teacher?<issue_comment>username_1: There is only one thing anyone can suggest and that is to report it. Tell your parents or tell one of your teachers, and if they don't do something for you, then tell the Police.

You should not have to accept this behaviour.

The school has a responsibility and duty of care to their students. They can support the student whilst reporting the teacher to the authorities and the school can notify other child safeguarding authorities to prevent them working in other schools

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_2: I suggest you should report it directly to the police.

Why, well, as he has been dismissed from the school they have no control over him, so reporting it to the school will only be for information.

You can choose to tell or not your parents but you may value their support.

I hope this sorts itself out. Best wishes.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_3: Following points may help you to get rid of it:

1. First and most important step is stop communication. Never reply to calls nor messages. Also never accept any kind of request from strangers in social networks nor reply to their messages. If they send message from a fake ID which looks similar to someone you know, then first confirm about it from the mutual friends or by phone calls before paying any attention to them.

2. Second step is tell to your parents, brothers and a lady teacher with whom you feel comfortable.

3. Third step is inform to your friends about it and tell them to stay away from that person and maintain distance.

4. Fourth step and may also be the very first step is inform to the head of your School about this matter and request to take possible action against him.

5. Last step is if nothing works for long time and things go to extreme, then report to police.

Hope this will help ....

Stay blessed!!

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_4: **Tell your parents**.

If my Googling is accurate, then 10th grade in India is about 15-16 years old. That's below adult age. Accordingly, don't try to resolve the problem yourself, tell your parents (or guardians) and let them resolve it.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_5: 1. Report this to the police.

If you live in a place without legal protections in this regard, it's still helpful to push the boundaries.

2. It would have been helpful to apply a consistent non-response policy. Given that you had trouble with this, I suggest handing your phone over to a trusted adult temporarily.

3. Please learn some basic online self-protection measures. I noticed that you created a StackExchange user account with a first and last name, and you posted your age and the name of your town in your question. Also, I wonder how the teacher found you online. Here's a starting point: <https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/online-id>

Upvotes: 0

|

2018/02/25

| 589

| 2,482

|

<issue_start>username_0: My interests are very broad. Before grad school I did a lot of things, but now it's expected that I only do one thing. Provided that I can demonstrate research competence in more than one field, by publishing for example, is it possible to write a thesis that consists of several smaller, orthogonal projects instead of a single great push? I understand why this isn't encouraged - diluting yourself is not an efficient way to get things done and it's unlikely that one would be able to become a PhD-level "expert" in more than one deep subject. But provided that one is very industrious and willing to give up the prospect of having any kind of normal life, which I am, has this ever been done?

Also: I realize this is funding-dependent - assume that I have external funding from a fellowship.<issue_comment>username_1: Ultimately, it is the University's decision what call a PhD thesis. While the widely accepted norm is indeed a large piece of independent work on a single question / topic, a "portfolio" of small but important contributions can be accepted in exceptional cases. These exceptions, however, are justified by the exceptional quality and importance of the work done, clearly demonstrating the candidate's expertise, skill and talent. Simply having family and kids is unlikely to be sufficient for the exception to be made.

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_2: It will depend on the advisor, the university (i.e., will they allow you to work in different fields. I mean, technically they can't forbid you to work on something, but your advisor might not be pleased with it) and the details of the topics (will it be **really** possible to work on a variety of them).

In general, a thesis should provide an answer to a research problem, either in the form of a self-contained *book*, or a [sandwich thesis](https://academia.stackexchange.com/questions/149/what-is-a-sandwich-thesis).

I'm also interested in many fields (which can be divided roughly into 3 main ones at the moment) that are not really connected to each other that much. My advisor told me to compose a thesis only about one of the topics (which I published 3 papers on), and **not** to make a mix of unrelated works (sounds reasonable to me). And that's how it was done (in the form of a sandwich thesis).

I added the papers on other topics to my CV, and they were useful when applying for a grant, scholarship etc. And of course for conference presentations.

Upvotes: 3

|

2018/02/25

| 414

| 1,806

|

<issue_start>username_0: I have done some work and want to upload that research work on Arxiv. The problem is that the second author wants to work more on this and doesn't want to upload the result to Arxiv. I am thinking that I will upload the result on Arxiv and then I will keep doing research on that thing, so if get more results, then along with the second author I will submit the result to a conference.

**Question:** Suppose I upload an article on Arxiv as a **single author** and after that I work on the same problem and get some results. Will it be possible to submit again the additional result with **two authors** on Arxiv and to a conference? Is there any problem with the process I have described above?<issue_comment>username_1: If the modified work is an extension of your arxiv article. Then yes. But in case the work stay the same you can't as you already reference the work as a single author.

Upvotes: 0 <issue_comment>username_2: I imagine that there is no problem from the side of arXiv: submissions there are versioned, so you can always update a preprint there. arXiv also explicitly allows you to submit the same work to a different venue later on.

The problem with your process is that you do not seem to have a trust relationship with your second author. If your second author does not want your joint paper uploaded to arXiv and (i) you do it anyway, and (ii) do not even make him an author even though he was part of the research, then what does this say about the relationship the two of you already have? And what does it say about the kind of relationship you hope to have with him in the future? If I were that second author, I would consider uploading a joint paper over my objections a major breach of trust. I would not ever want to work with you again.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/25

| 864

| 3,444

|

<issue_start>username_0: Say I find a Math Proposition in another paper, which is just stated, and no proof (nor even sketch of proof) is given.

If I am writing a paper referencing that paper, is it good or bad (from reviewer's point of view) for me to fill in the proof of that proposition?

If I do so, what is a good way for me to indicate it in the paper? (that the proof written is by me, though the proposition is by the other paper)

The proof is not trivial, though it is not particularly difficult either.

Or should I just privately verify if the proposition is correct? And just cite the proposition (without proof) in my paper?

Thanks.

I am concerned about this issue since I followed the news story in the case of <NAME>'s proof of Poincare conjecture; the authors who filled in "gaps" in his proof did not go well with the reviewers and the general public. (<https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/08/28/manifold-destiny>)<issue_comment>username_1: Let's call the other paper [A].

First of all, you might like to check whether a proof already appears in some other paper or book, [B]. You can search MathSciNet or other databases for papers which cite [A]. If so then you can cite both ("The following proposition was stated in [A]; see [B] for a proof.")

Otherwise, whether to give a proof is at your discretion. If you think the reader would find it helpful to see the proof, and it doesn't distract from the main purpose of your paper, and it isn't excessively long, then sure, you can include it. People often use phrasing like:

>

> We make use of the following proposition, which is stated in [A]. Since [A] does not include a proof, we give one here.

>

>

>

Another option is to put the proof in an appendix, or to write it up as a separate note which you post on arXiv or something.

The Perelman case is about something different - people disagreeing over whether the original paper actually solved the problem, and how much of the credit for the result is due to those who filled in whatever gaps there may have been. In this case, you describe the proof of the proposition as "not particularly difficult", so it's likely that the authors of [A] did in fact know how to prove it, and so would most of their readers who took the time to do it. It's reasonable to give all the credit for this proposition to the authors of [A]. There's nothing wrong with you including a proof, and as long as you don't try to take credit for the result, no controversy will result.

Upvotes: 6 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_2: I don't think the situation is at all comparable with the news article you linked. You're not claiming that you should get or share the credit for this proposition, you're not saying that the cited work lacks critical steps that you're fixing. (I also don't think that the proposition in question is a century-old, world-famous conjecture.)

If the proof is really "not particularly difficult", then I see no problem either way: cite the proposition, and then either write your own proof or leave it at that.

But you shouldn't worry about any kind of backlash if you decide to write your own proof. People rewrite proofs all the time for a variety of reasons (you want to match it to your notations, your hypotheses are slightly different, you want to reuse the steps and ideas...) You would have to write this in a rather obnoxious way to encounter any repercussions.

Upvotes: 4

|

2018/02/25

| 616

| 2,630

|

<issue_start>username_0: So I am applying for a postdoc position and I happen to be working on a problem that is quite closely related to PI's interests. I don't just mean that we share the same field/subfield (which we do anyway) but rather the problem that I worked out is an advancement of what he (and some other people) is doing. This makes my case particularly strong since he wants to work on related questions.

Now, I recently uploaded a preprint of my this work and I was thinking that if I highlight this paper in the cover letter for the application, my application would stand out. Including a direct link to the preprint sounds like an option to me. However, I have never seen a cover letter with links to papers. Is this possible and acceptable?<issue_comment>username_1: While I've only been on the applicant side of things, I expect that it would be fine to include a link. Different PIs will react differently, of course, but it seems unlikely to ruin your application. Just make it clear from typesetting that it is a link. Given that the PI might only look at the printed version you should probably make the link text self-explanatory as well, e.g. using an arXiv identifier. However, depending on the method of submission you might be able to just attach the preprint of interest to your application. I expect that this is the ideal approach, when possible.

As support for using links, see this [Nature Jobs blog post](http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2014/02/28/make-your-cover-letter-and-cv-stand-out/)

>

> When you’re reading an article online you’ll often find links to relevant content that is outside the article. This technique can be used in your cover letter too. Use links to information such as your research lab website, or your online portfolio and research papers. You can even link to specific papers that have been highly cited or extra-curricular projects you’ve been a part of. Let the employer know that there is so much more to you that what appears on that flat piece of paper!

>

>

>

Upvotes: 4 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_2: If you describe why your recent research work is significant and relevant to your application, **and if it's significant to actually look at the paper itself**, then why not? As someone who reads an application I'd find it quite reasonable.

On the other hand, I've set the key sentence in boldface. If it's not obviously important to go look at the paper itself, then providing the link seems weird at best, or vain at worst.

Caveat: I'm not tenured and don't have experience reading cover letters, only writing a few of them.

Upvotes: 1

|

2018/02/25

| 241

| 1,007

|

<issue_start>username_0: Can anybody explain why someone who is editor of a reputable journal also act simultaneously as an editor for a potentially predatory journal?<issue_comment>username_1: We cannot know if this is really the case, but many disreputable publishers surreptitiously list well known scientists in their editorial boards, without asking their consent.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_2: The editor is the only person that knows for sure. Some possibilities (note I do not know if ikpress is a flaky publisher - I'm simply assuming it is):

* He doesn't think ikpress is a flaky publisher. Compare Frontiers and MDPI, both publishers that were included on Beall's list that also had established academics defending them.

* He isn't aware ikpress is a flaky publisher.

* He doesn't care that ikpress is a flaky publisher (for whatever reason).

* He doesn't know he's listed as an editor, or he might have tried to be "unlisted" but the publisher has been slow at removing him.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/25

| 553

| 2,173

|

<issue_start>username_0: I’m on my 3rd/5 undergraduate years, so I’m just starting to think about grad admissions.

I’ve been planning on applying to MD/PhD programs. I enjoy/feel comfortable in hospitals and think I can make a contribution or two in medically-relevant bioinformatics/comp. genetics.

So, one of the big pulls for me into a grad program is teaching. I would probabaly enjoy being a high school teacher or a college lecturer but it seems like an insecure career path to me, and not doing *any* research would probabaly bum me out after a while.

And, in theory, MD/PhD programs support that—TAing, teaching classes, teaching workshops at conferences, simplifying complex ideas for patients, etc. MSTP guidelines even mention teaching interest as an important characteristic.

But, in practice, I feel weird about emphasizing my teaching interest. Most grad students I meet dislike being a TA, professors don’t like teaching, and often it seems like they feel like teaching gets in the way of their *real work*. And those are the people who will be reviewing my application. I’m kinda afraid that I’ll be seen as a not-serious-researcher for wanting to focus on teaching.

Should I de-emphasize my teaching interest? If not, do you have any suggestions about how to present it on personal statements/interviews/etc?<issue_comment>username_1: We cannot know if this is really the case, but many disreputable publishers surreptitiously list well known scientists in their editorial boards, without asking their consent.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_2: The editor is the only person that knows for sure. Some possibilities (note I do not know if ikpress is a flaky publisher - I'm simply assuming it is):

* He doesn't think ikpress is a flaky publisher. Compare Frontiers and MDPI, both publishers that were included on Beall's list that also had established academics defending them.

* He isn't aware ikpress is a flaky publisher.

* He doesn't care that ikpress is a flaky publisher (for whatever reason).

* He doesn't know he's listed as an editor, or he might have tried to be "unlisted" but the publisher has been slow at removing him.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/25

| 2,645

| 10,930

|

<issue_start>username_0: This issue is about a university in a 3rd world country.

I friend of mine (I will call her "Z") is a faculty member at a reputable university. During one of her sittings with an undergrad student ("A"), she learned that another faculty member ("T") is sending "A" some inappropriate text msgs and emails. "A" also mentions that she has heard similar stuff from another student "B" about "T". "A" offers to show some texts to "Z" to which "Z" refuses. But "Z" does tell "A" that office of student affairs handles such matters to which "A" says that she is aware of that office but does not want to report. "A" just wants to graduate ASAP and thinks that "T" might damage her as he is quite powerful within school administration. Therefore no action.

I am convinced that, given "A" is not the only student who is being harassed, "T" will misuse his position and will continue his inappropriate behavior. And I am also convinced that office of student affairs will take action **if notified**. I guess that my friend "Z" does not want to be a whistle blower although she thinks that "A" is being truthful.

I think that keeping quiet will only make things bad for other vulnerable students. Please mind that for a female going to university in that country is a privilege. And "T" is not on the university's radar. So I am thinking of dropping an anonymous email to office of student affairs. Is it ok to do such a thing? I mean I have not even an iota of business with that university, "A", or "T".

So my question is:

***Is it ok for a person, who has nothing to do with any of characters in the story, to drop an email asking administration to take a look into these allegations?***

**Note:

I understand that accusing anyone wrongly has serious consequences, both professionally and personally. But at the same time if these allegations are true and are left unnoticed, students and the university will be at the receiving end.**<issue_comment>username_1: This is going to vary massively based on opinion. Still, my reaction is to **do nothing**. A or B have to stand up for themselves, otherwise for others it's a case of wanting to help but not being able to do so. Imagine what happens if an uninvolved third party writes to the administration asking them to act:

1. The administration has to take the allegations seriously. To convince them of that, you need to provide evidence. It seems like you don't have any solid evidence, only 2nd-hand information.

2. Assuming the administration takes the allegations seriously, they're likely to want to interview A and B. If A and B refuse to cooperate, the administration can't proceed.

3. For the administration to proceed, they need to make A and B cooperate even though they've stated (at least in A's case she has) that they don't want to. Are you sure that you want to put them through this?

Another thing to mention is that you could be accused of betrayal of trust. Z can plausibly argue that she told you this expecting that you will keep it confidential (it is likely A told Z expecting Z to keep it confidential, too). If you report to the administration and they press you about this, what can you say?

I would talk to A & B, argue that they should raise the issue to the administration both for themselves and for others, but also defer to their decision.

Upvotes: 4 <issue_comment>username_2: As [username_1](https://academia.stackexchange.com/users/84834/allure) points out, opinions on this matter will vary, so let me note some points that I think are important here, and also offer an opinion that is slightly to the contrary of some other answers. (For brevity, these points are framed as an answer to the person you are talking about who is the academic dealing with these students.)

* **Academics have a duty of care to students:** Students at university are adults, but they mostly are still young and inexperienced. In my humble opinion, academics should generally err on the side of *pushing for assistance* in cases like these, even if the students are reluctant. Students are generally young adults who may be intimidated by the positions and standing of older adults who have attained academic success and institutional power. Having another academic push the matter forward may be helpful in overcoming this disparity.

* **Harassers thrive on the "I won't make a fuss" mentality:** Without making any assumption about whether or not harassment has actually occurred in this case, it is worth noting that cases of harassment tend to be done over and over again by a small number of individuals, and tend to proliferate because each person who is being harassed thinks it is only them, and they don't want to make a fuss and risk retribution by a powerful person. In cases where a victim of harassment reports the conduct, it is not unusual for this to precipitate an avalanche of other allegations against the same harasser. Recent events in Hollywood (e.g., <NAME>) testify to this fact, as do many other cases of sexual harassment.

* **Merely referring an allegation is not "accusatory":** Reporting an allegation *for it to be investigated* need not presume the truth of the allegation, and need not be "accusatory". That is the point of an investigation - to get to the truth from a starting point of it being unknown. It is perfectly legitimate to report allegations you have heard on to the administration, while taking no position on whether they are true or false, but still asking the university to consider whatever investigation into the matter is warranted by the allegations. There is no contradiction between wanting to bring this matter to the attention of the administration, and also wanting to avoid a false accusation. Just make sure that if you do send an email to the administration, you write it in a neutral way that does not presume that misconduct has occurred.

* **In the end, evidence will be required:** While it is legitimate to report hearsay allegations for the purpose of bringing a matter to the attention of the administration, you should bear in mind that your hearsay is not evidence. Unless one of the affected students is willing to speak to the university administration about this, the university will probably be very limited in its ability to investigate the matter. That is perfectly legitimate - after all, people should not be subject to negative proceeding against them without evidence, and hearsay evidence is weak evidence.

* With this in mind, the contribution you can make here is to bring the allegation to the attention of the administration, leading to contact with the students, and giving them an opportunity to report this matter formally. By acting as the initial referrer of the allegation, you can also show your students that actions are louder than words - you are willing to get involves, so maybe that will make them more willing. Still, at the end of the day it will depend on them. In my view even this step might be a good idea, even if the students ultimately decide not to proceed. I don't agree with the recommendation to do nothing.

* **Have the courage to put your name to the referral:** Think carefully about whether it is appropriate to report this *anonymously*. If it is justifiable to refer the matter to the university administration, and if you frame your email in a fair way that does not presume misconduct, then you ought to have the courage to put your name to it, and stand by your own actions. Reports of harassment are generally treated in confidence (at least up to the point where the accused is able to face the accusations), and this is an opportunity to set an example for your students and show that you are willing to act on your own principles. If a grown-up academic can't show the backbone to make a report about a colleague, without hiding behind anonymity, why should younger students show the courage that is absent in their elders?

Anyway, that is my two-cents. I'm sure there will be plenty of others with contrary opinions. Hopefully others will also give their views, as it would be worth getting some contrary ideas on this matter before making your decision.

Upvotes: 6 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_3: I don't think you *can* do anything, ethically. At least not in the way you are considering.

You write that "accusing anyone wrongly has serious consequences",

and "students and the university will be at the receiving end",

but have you considered the consequences for the student "A"

and for your friend "Z"?

The student "A" has said that she does not

want the stress and possible problems that

reporting the faculty member "T"

would cause. Maybe she *should* report him,

for the sake of other students, but she has decided that she doesn't

want to, or perhaps can't. Do you want to force her to this,

possibly even ruining her education? Who knows how she will react?

It should be her choice, not yours,

so you shouldn't name her.

Your friend "Z" didn't want to see the evidence, and doesn't want

to get involved. "Z" has made a similar decision as "A", for

unknown reasons. Again, her choice, not yours.

It seems to me that what your anonymous letter

should then say is something like this:

>

> Hi, I am an unidentified person, who heard from an unidentified

> faculty member at your university that an unidentified student

> at the university claims that faculty member "T" is sending

> harassing text messages.

>

>

>

I don't think that will be very helpful.

You *can*, however, encourage your friend to take a more active interest, and try to get the student to report the harasser, perhaps waiting until after she has graduated.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_4: >

> Is it ok for a person, who has nothing to do with any of characters in the story, to drop an email asking administration to take a look into these allegations?

>

>

>

Since the country isn't listed, there is no way to provide any definitive legal or even cultural answer to this question.

However, aside from any legal or cultural specifics, this is a matter of conscience for "Z" to deal with personally. "Z" should consider whether they can live with their decision after considering the possible ramifications of their decision.

* If "Z" does nothing, is "Z" prepared to accept that there may be future students that will be subject to such harassment that could have been prevented?

* If "Z" does nothing, is "Z" prepared to accept that such harassment (either now or in the future) may escalate beyond inappropriate texts/emails that could have been prevented?

* Is "Z" prepared for the possibility that this becomes a public scandal in the future and that "A" may make public statements that they confided in "Z" and that "Z" did nothing?

If "Z" cannot comfortably answer yes to these questions, they really should report the allegations to the office of student affairs.

Upvotes: 2

|

2018/02/26

| 4,035

| 16,277

|

<issue_start>username_0: I am a third-time postdoc, and had never before had problems with getting paid. For almost two years now I have been a postdoctoral fellow at a university in southern China. This is my first experience in Asia, and thus I am not sure of how common the situation I am facing is. Communication is arduous, not due to language differences, but a number of cultural traits which are hard to explain.

At the end of my previous contract, I contacted many institutions for job opportunities. I did not plan on accepting yet another postdoc, but these colleagues here convinced me (> 100-long-email negotiation) that I'd be paid a good salary, enjoy a good work environment, and easily take an assistant professor position as soon as conditions allowed. To make it clear, I signed a postdoctoral fellow contract for a 120k RMB salary per year, with a promise of an extra 60K RMB per year to be provided by the college. There are some extras on the contract, such as 10K RMB for purchasing a laptop, and reimbursement for moving expenses (to date, I never saw those).

I was instructed to apply for a visa after signing the contract. I needed a certain official document about which they claim they were unaware. After further email exchanges where I had pictures and links about the document, it took 2 months to get it by mail. This delayed my arrival btwo 2 weeks from the start of the contract, but over email they said that was no problem. In reality, they never paid me that 1st month while dismissing it by saying "probably will fix that later".

Another full month came without any pay, and apparently the administration couldn't agree with the bank on spelling my name, but I never knew the details. After many trips to the administration to find out what was wrong, I was paid ca. 5,500 RMB for the month. I tried to complain but no one would understand me. Then the confusion started.

I will try to summarise below as best as I can. It is really complicated, and everyone tells me "not to worry".

* I get paid ca. 5K RMB as fixed salary on the 5th-6th every month.

* Around the 25th they pay me another instalment which is highly variable, typically within 1.5K-4.2k RMB. (Tends to be higher before long holidays).

* After one year I got ca. 90K RMB, irregularly paid out of the contract's 120K.

* Only after aggressively complaining, hinting a lawsuit, I received 100K out of the promised *extra* 2x60K. (divided in 3 irregular transfers, made by some 18-y-old undergrad, late at night)

I get more info only by pressing uncomfortably hard. I was once told I'd get 13 payments per year (*never happened*). Then I was told some unspecified **large sum is retained to fund my expenses to any trips/conferences** I might wish to attend. I was not clearly informed of when or even if I would get the withheld amount. Few other postdocs openly discussed this problem with me, and they said (one Chinese and one foreigner) they had the same issue. The Chinese postdoc recently was offered to move to a new salary regime where he now gets a fixed, higher salary (took him months to tell me).

To make things even more complicated:

* I have found in my internal access system some separate account originally containing 40K RMB under my name (some "funding" mentioning my name), which is being used to apparently pay internal procedures. Upon asking about it, I was told to "not worry about that". There are currently <20K RMB left in this virtual account.

* A PI which is not the person I dealt with over emails is the person who signed my contract. According with local standards I am then supposed to consider him my "leader". This person is frequently absent, shows no interest in what I do, and refuses to reply any email about my salary/project. Now *I am pushed to list this PI's name as last author* in anything I write. My first paper from here is about to come out, and at the last minute I am requested to ask the editor to finally list this PI as the **corresponding author**.

I feel like I am being constantly blackmailed over retained promised salary payment. My visa expires in a few months. They passively owe me >80K RMB and I do not know what to do. I hear that suing is usually not advisable in China as lawyers ask for huge fees and judges tend to favor local standards and influential institutions/persons, plus the defendant will typically delay forever by refusing to engage.

I wish to ask whether anyone here had a similar situation, and would know what could be done? Particularly in China?

Before you ask: further unmentioned issues not directly related to salary finally did not make this a "healthy work environment". I am now informally told that "it is really hard for foreigners to get accepted locally as assistant professor because getting a major NSF grant is required, and that depends on significant connections (*guanxi*) and understanding of Chinese language/culture". Not that I was planning on staying longer, but just to clarify.

**\* UPDATE \*** 02/04/2018

I finally left China yesterday. I will summarise the chain of events and the current situation. I think I understand most of their scheme now.

About two months prior to my departure I started pressing the administration about the rest of the salary. They insisted a large, unspecified part, would be paid as soon as I finished all necessary exit procedures correctly. Moreover, the secretaries said a part of the payment would be retained as "taxes," but they were unable to specify what percentage nor type of taxes. Exit procedures included preparing lengthy reports which had not been requested before. At the same time they further reduced my salary, interrupting the last "2nd parts of salary" due to "unforeseen reasons" and said they'd try to fix that also at the very end!

After I quickly assembled reports and delivered all documents (signed by several professors who make it clear they are making some favor), the administration agreed to finally calculate how much they owed me. I went there several times only to hear back more nonsense. For instance they kept remarking they might not pay me for the last month "because I had delivered a final report prior to the end of the contract period" as they instructed!

Finally, after pressing them considerably, within 10 days of my departure they provided me their numbers. They would pay me a "reward" for completing documents, plus one month of basic salary, and promised a large sum adding up to the final amount... in exchange for **invoices**.

I confirmed with responsible PIs the need for invoices. They explicitly instructed me to *buy invoices* from companies they'd recommend by paying 10-15% of the declared value to "reimburse the rest of my salary". They insisted this is common procedure, offering help to "find invoices to exchange". I was shocked and refused.

I went to the Principal Office with a complaint letter, in English and Chinese. I spoke with the sub-secretary for 1h. They explain that what is declared on the contract as salary includes a significant amount which is to be spent with research only, and that invoices ensure the university can pay/reimburse. They say this is detailed in rules in Chinese in some book somewhere if anyone had questions. I made it clear nobody had ever clarified that, it should be explicated in the contract, and that I could not deal bogus invoices in exchange for payment. I told them I could only provide true invoices, which they accepted as a clean solution. They thanked me for "bringing me a major misunderstanding to their attention".

Finally I purchased credit for services with biotech companies with about 5k USD off my promised contractual salary. Got the "rewards" plus some delayed payments. It is not crystal clear from the numbers where is the last month of payment (I haven't had the guts to sieve that now).

After being paid I contacted my Consulate reporting the events, letters. Mainly to ensure some authority was aware in case of any political revenge (e.g. unfair accusation, arrest). I finally left without any events. I avoided physical contact with the PIs, who refrained from answering any further emails after I refused to purchase invoices. A few hours ago the Consulate notified the situation to the local Foreign Affairs Office, and emphasised it looks very serious.

**This is where I stand**. I hope something will be done to at least stop these schemes ongoing with other postdocs. I am moving to publish the story in the international press, and possibly file everything to the Ministry of Education right after. I thank everyone here for providing insights and suggestions. Keep an eye on the news.<issue_comment>username_1: Your first stop should be: Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security

中华人民共和国人力资源和社会保障部

How you will contact and make a complaint without knowing of Chinese language, I am not sure. I would suggest you a lawyer, but the culture is not the same, so what is consider lawyer in West it is not considered as usual in China.

there is also Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

Also, there is Ministry of Supervision 中华人民共和国监察部

I mention them because the information you provide clearly indicates misuse of public funds.

if you dont know the Chinese language I recommend going for help to Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. they should know English and they can advise you where and how to complain.

Upvotes: 4 <issue_comment>username_2: Invited by the OP to post my comment under another post here:

Courts in China are often unwilling to rule in favor of foreigners in economic dispute cases. Not to mention that Chinese law already provides inadequate protection for workers in this case. I am not a lawyer myself, so I do not feel qualified to talk about the legal details, but in general it is very hard for workers to get what they deserve when they end up in a wage dispute, and especially if you're foreign. (Source: a close family member has experience working as an attorney-at-law in many wage dispute cases, including a few involving foreigners).

China can be pretty unfriendly for foreigners living in the country, as there are a lot of limitations on them. I would not suggest avoiding the country, but do expect a lot of difficulties.

---

**More**:

To solve this problem, you do need to know some Chinese politics. In China, universities are placed under direct administration of either the Ministry of Education or the provincial Department of Education, and they have no administrative autonomy whatsoever (unsurprising, because there is no separation of power in the Chinese government system, even on paper).

So, a court might not solve your issue. The court, as another government agency, would be unlikely to rule against another government agency. Also, this is a case of economic dispute and you are a foreigner. If you really want to go to court, find an experienced lawyer. Note, however, that Chinese courts can forbid foreign citizens with unresolved civil litigation from leaving the country; if your bring the case to court, you might risk not being able to leave the country until the case is resolved.

You might have a better chance if you *escalate* the issue to a higher level governmental agency. The Ministry of Education 教育部 might be a good choice (they likely are your university's direct supervising agency), so is SAFEA 国家外国专家局. Do try to contact them.

If you think there's corruption involved, try the Communist Party's Central Commission for Discipline Inspection 中央纪律检查委员会 (aka 中纪委). The Ministry of Supervision (now the National Supervision Commission) is in fact just another name under which the CCDI operates, so no need to contact them individually. The CCDI is an extremely powerful agency, so they might be the most helpful to you (of course, that's if they do take your case seriously).

Do write a letter to the CCDI if you are confident that misuse of public funds is present. However, instead of writing to your university's president 校长, perhaps writing to your university's Party Secretary 党委书记 might be more helpful. Also, see if there's a Central Inspection Group 中央巡视组 inspecting your university. If there happens to be one, you might as well report to them directly.

Do consult a lawyer. Be sure to choose a lawyer with experience working with foreigners.

Upvotes: 6 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_3: >

> I wish to ask whether anyone here had a similar situation, and would know what could be done? Particularly in China?

>

>

>

I might add my feedback on this, comparing it to my experiences. I've been a postdoc at Nankai in Tianjin, and have worked here ever since. I love China!

Miscommunication is normal here: you plan your life and career based on the information they provide, only to find out what you envisaged is incorrect. If you're particularly concerned about money, China is probably not the place to be.

>

> I signed a postdoctoral fellow contract for a 120k RMB salary per year, with a promise of an extra 60K RMB per year to be provided by the college.

>

>

>

I'm an associate professor with years of experience working in China, many Chinese co-authors, and a fellowship; I'm a native English speaker, I speak Chinese (sort of), and I have a Chinese green card. Regardless, this salary would be higher than my current salary. Very few postdocs (any?) in China will get such a high salary.

>

> I needed a certain official document about which they claim they were unaware.

>

>

>

This happens a lot: rules and regulations change in China quite frequently, and officials don't update the websites (both the Chinese and English ones). It's normal to find out mid-way through an application that something else is required.

>

> In reality, they never paid me that 1st month while dismissing it by saying "probably will fix that later".

>

>

>

I arrived in January, started getting paid in May, and they backdated it to March. During this time, I wrote papers which would probably impact me far more than a few months salary. I also get to live in China! China!!

I also didn't (and still don't) pay rent as the university covers my accommodation, and I barely pay bills.

>

> Then I was told some unspecified large sum is retained to fund my expenses to any trips/conferences I might wish to attend. I was not clearly informed of when or even if I would get the withheld amount.

>

>

>

I've racked up some huge travel bills: 9 countries this year; 10 countries last year. The payment of flights, accommodation, and registration is usually done by the university, so I don't have to do much. That's quite a lot of life experiences!

>

> ...everyone tells me "not to worry".

>

>

>

I've learned not to worry. I just work hard, gain experience, and publish, and money sorts itself out.

>

> Exit procedures included preparing lengthy reports which had not been requested before.

>

>

>

I was asked to write a report at the end of my postdoc too (something like 70+ pages); something like a "postdoc thesis". I copy/pasted my papers into it, put in a whole bunch of conference photos, etc. Nobody is ever going to read it.

>

> They would pay me a "reward" for completing documents, plus one month of basic salary, and promised a large sum adding up to the final amount... in exchange for invoices.

>

>

>

I've never heard of this. Here, invoices are needed for reimbursement (e.g. for hotels, taxis, etc.), but never anything else.

>

> They explicitly instructed me to buy invoices from companies they'd recommend by paying 10-15% of the declared value to "reimburse the rest of my salary". They insisted this is common procedure, offering help to "find invoices to exchange".

>

>

>

I've never heard of it. I'd probably refuse too.

>

> They explain that what is declared on the contract as salary includes a significant amount which is to be spent with research only, and that invoices ensure the university can pay/reimburse.

>

>

>

That explains the extraordinarily large salary, and the mysterious invoices.

It sounds like your colleagues were trying to find a "workaround" ("buy invoices from companies they'd recommend") so you can claim the research-allocated funds.

Upvotes: 3

|

2018/02/26

| 1,072

| 4,245

|

<issue_start>username_0: I have sent a paper to the journal that was predatory and I had no idea what that was. Today, they sent me an email that I need to pay **1819 euros** to publish my manuscript. On their internet pages stands that publication fee is 1819 USD and **1705 euros**. This means that they have changed their "price". They also said that in case of withdrawal I will need to pay 919 euros and that it is a half of price (919 euros is not 50% of above mentioned fees). If i do not pay, what could be legal consequences for me? Please help.<issue_comment>username_1: Based on the available information it is not possible (or even allowed?) to give legal advice. However, I **strongly** recommend you to contact your institute's legal department/lawers for support. You should also talk with your supervisor/professor about this, they might have experience.

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_2: You look at a contract problem. Do you have a written or implied contract with the journal? What jurisdiction are you and the journal under?

Given the fact that the disputed value is 919 euro, I guess the problem is rather academical.

Here are possible outcomes:

1. Nothing happens, you don't pay them, they don't publish the paper.

This is the most probable.

2. You don't pay them, but they sue you

(where?) for the 919 euro amount due. As a variation, a local (to

you) collection agency is involved. Disputed amount would be larger,

as it includes collection fees and judgement. If they sold the "debt" to the collection agency, they are the plaintiff and you are the defendant. Odds are they will obtain a favorable judgement and you will pay.

3. They publish the paper

anyway, and sue/collect you for the full amount. Odds here are you will get the favorable judgement, but you look at a few lawyer billable hours.

Ultimately, you are the one having "a change of the hearth" as you submitted the paper and you want it withdrawn now. The journal doesn't seem to be at fault at all until now.

Upvotes: 0 <issue_comment>username_3: **Get legal advice**. I don't see any other way about this unfortunately. They could easily say the 1819 EUR charge was a typo and it should've been 1819 USD. It also clearly says on the website that there's a withdrawal charge, although it doesn't say how much. They have removed the reason for the withdrawal charge from their website; however I'm sure I saw in previous versions of the page that the reason is you've taken up the editors' + reviewers' time, which is a defensible argument.

You may have to provide an explanation for why you submitted an article to them in the first place. If you can e.g. point to a deceptive call for papers which did not mention the article processing charge, you have a stronger case.

Having said that, don't worry too much, you're probably going to get away without too much pain. Reasons:

* The publisher is OMICS, which has a reputation as *the* worst predatory open access publisher out there (see their [Wikipedia page](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OMICS_Publishing_Group)). You can point to action by the US government against OMICS, which should be especially relevant if you're based in the US.

* Because OMICS is so bad, there're likely to have been many authors who wanted to withdraw their articles. If OMICS has initiated legal proceedings against these authors, I'm not aware of them (and they would undoubtedly have been publicized by the victims).

* OMICS has already been involved in lots of legal suits, on the wrong side (i.e. they're the defendants). Courts are not likely to be sympathetic to predatory OA publishers.

* OMICS has little to gain by filing a suit. The most they can hope for is 1819 USD. That's probably not enough to be worth the effort.

I'd guess that the most likely result is that you'll be blacklisted by OMICS. They might refuse to consider any more of your papers or they might charge higher article processing charges the next time you submit an article. They might even take you off their mailing lists. Do you care? One might even send them some genuine thanks if they do.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_4: Pull the paper. Don't pay the withdrawal fee. Stop submitting to such junky journals.

Upvotes: -1

|

2018/02/26

| 496

| 2,076

|

<issue_start>username_0: I've submitted the final manuscript for a book with a reputed social science publisher. My publisher wants a list of people who might be willing to provide endorsement for the book.

Whom should I suggest? In particular, is it appropriate to suggest people I've been working with, for example my supervisors? On the one hand, they would not be neutral, but on the other hand, that seems to be precisely the point of an endorsement. Should I approach them myself before suggesting them to my publisher?

I'm not sure what exactly "endorsement" means, but I believe it's about writing one of these "blurbs" that you see on the back of some books. In any case, the purpose is for marketing, not for scientific review.<issue_comment>username_1: As publishing has also a commercial side, publishers do want to get their costs paid (and they hope for some profit). So, they want to ensure as good as possible that someone (libraries, institutes, ..) will buy the book. For that you need your endorsements.

There is no problem in taking you supervisors for endorsement. However, I would advise you to personally ask them for their support.

Furthermore, it would be helpful if you find some other people that may to the same - have you been to conferences, spoke with people - do you built up a personal network with other peers? If so, ask them. They should be well known people in the subject you are publishing, of course. Reputation sells.

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_2: An endorsement isn't necessarily the blurb at the back of the book - the blurb can also be written by the author. It can be a book review printed at the back of the book, or in some magazine or journal that is willing to publish it.

In general the more famous the endorser (or the magazine / journal), the better. Prestigious titles (e.g. "Astronomer Royal") or affiliations help also. It's OK to suggest your supervisors - endorsements are not neutral. As for approaching them first, you know your supervisors better than most people, so you can answer that best.

Upvotes: 1

|

2018/02/26

| 1,087

| 4,594

|

<issue_start>username_0: It could also be placed on <https://english.stackexchange.com/>, but I feel it is more suitable here. So: **Is there a term for the (trivial) fact that research is done only with the means available?**

For example a mineralogist won't study stones from the Moon if s/he doesn't have one. More specifically to my case: I am looking for a term that describes the problem of researchers who want to do something, but cannot do it by hand and not even by computers due to lack of suitable software/hardware (e.g. inverting very large matrices); and as a consequence they don't do it. (And in a verly last step, I want to find out whether there is research done about the consequences on science due to lacking software/hardware.) Is it simply called "lack of technology" or something similar?<issue_comment>username_1: "practical limitations" could cover just about any type of situation where you don't have the means to do what you'd ideally like to do.

"resource limitations" could cover not having enough time, money, or trained people to do the work, not having the right equipment, and a lot of other things.

"equipment limitations" could cover not having enough equipment, or the equipment you have can't do what you need.

Upvotes: 6 [selected_answer]<issue_comment>username_2: In my university, people often call limitations as 'constraints'.

I have heard them saying:

"resource constraints" - availability of computers and machines, people

"financial constraints" - Money

"space constraints" - Physical space (room), lab etc.

Upvotes: 5 <issue_comment>username_3: I would lean towards words like tractability/intractability to describe problems. A problem that is intractable can, in theory, be done but, in practice, is not possible. For instance, you mention inversion of a matrix - in theory, the steps and processes required to invert a matrix of any size are clearly defined - it just is a matter of resources and time. However, in practice, the amount of resources and time required are unacceptably large.

Wikipedia has this to say about the [matter](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computational_complexity_theory#tractable_problem):

>

> A problem that can be solved in theory (e.g. given large but finite resources, especially time), but for which in practice any solution takes too many resources to be useful, is known as an intractable problem.[13] Conversely, a problem that can be solved in practice is called a tractable problem, literally "a problem that can be handled". The term infeasible (literally "cannot be done") is sometimes used interchangeably with intractable,[14] though this risks confusion with a feasible solution in mathematical optimization.[15]

>

>

>

which seems to reasonably approach what you are trying to express.

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_4: The problem you're describing at the end of your question could be considered a specific case of the [streetlight effect](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streetlight_effect):

>

> The streetlight effect is a type of observational bias that occurs when people are searching for something and look only where it is easiest.

>

>

>

This term is derived from a joke:

>

> A policeman sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlight and asks what the drunk has lost. He says he lost his keys and they both look under the streetlight together. After a few minutes the policeman asks if he is sure he lost them here, and the drunk replies, no, and that he lost them in the park. The policeman asks why he is searching here, and the drunk replies, "this is where the light is".

>

>

>

Usually this term is used to criticize over-reliance on convenience samples, but it can apply equally to convenience methods. Only studying the phenomena that you have the technology to study effectively (and therefore missing potentially important insights that would have required better technology) could be considered an instance of this phenomenon, albeit a very understandable one (you're not just looking where it's easiest, you're looking where you *have the technology to look*).

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_5: The angle that I immediately thought of before reading your example of limitations of compute power was limitations in available data. The phrase to describe that is **found data** or **observational data**. For example, you can't intentionally infect a person with a known fatal disease to study it, so there are fundamental limitations on the research, and it can only be done with the observed historical data available.

Upvotes: 1

|

2018/02/26

| 1,874

| 7,413

|

<issue_start>username_0: I'm a graduate student and I am really worried about the quality of my master thesis. It's my second year in graduate school and I've already done some pilot studies. But, entering the school, I was absolutely new in the real science (cognitive psychology) and now I'm afraid that data I collected is too dirty and statistical analysis I provided just incorrect. I have to present and publish my results anyway if I want to end graduate school and become a phd, but I feel ashamed of them.

So, I wonder is it ok to have problems with data when I'm just studying or I should refuse to publish or present these results?

My supervisor thinks everything's great and local journals will accept papers, but it is just bad, isn't it?<issue_comment>username_1: Since your supervisor thinks that everything is fine, you should *not* be ashamed of publishing your results.

If you are still unsure: You should talk about your concerns to your supervisor and request an honest opinion. Keep in mind, that he/she is also (partly) responsible for the quality of your results!

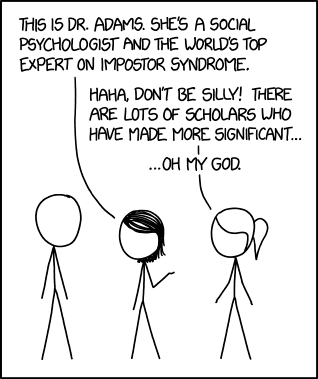

Upvotes: 5 <issue_comment>username_2: Imposter syndrome

-----------------

>

> I am really worried about the quality of my master thesis

>

>

>

This is normal. You are still being educated in your field, but working alongside professionals, reading professional papers; this means you're judging yourself against an unduly high standard: of course your pilot studies are not "as good" as a "finished" piece of work from professor or a postdoc.

This can cause, and be compounded by, [imposter syndrome](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impostor_syndrome). In imposter syndrome, you fail to correctly judge the standard of your own work (or set your standards unduly high) and, as such, underestimate your own ability leading to the feeling of being an "imposter". This is incredibly common - most (non-sociopathic) academics will experience it at some point in their careers!

To overcome this (and to identify when perceived concerns are actually valid) it is important that you take on board feedback from your colleagues. Your peers (the master's and PhD students you directly work/collaborate with, attend class with etc.) and supervisors/lecturers will be able to help you identify your strengths and weaknesses. Most importantly, they will be able help you overcome the imposter syndrome by providing a realistic judgement of your skills. In your case, the feedback mechanisms are suggesting that everything's fine:

>

> My supervisor thinks everything's great and local journals will accept papers

>

>

>

---

How to judge/assess your own work

---------------------------------

>

> I'm afraid that data I collected is too dirty and statistical analysis I provided just incorrect

>

>

>

The best way to deal with this situation, is as follows

* Make a list of **specific** problems you perceive in your analysis (e.g. should have used this kind of hypothesis test, should have compared these variables).

* Make any easy fixes (running a T test, for instance, can often be done quite easily).

* Now consider whether the remaining "problems" seriously undermine your conclusions.

+ Do not use perfection as your standard for this: nothing in research is ever finished or complete, especially "pilot studies"; just consider whether the data supports your conclusions.

+ Consider if you can resolve any undermining by hedging or changing your conclusions (e.g. "x causes y" --> "x show strong positive correlation with y")

* Look at published papers - is your analysis of comparable methods/standards? Have you performed a similar level of rigour?

* **Listen to your supervisor's advice**. They're the expert. They've published before. If they think the paper's fine, it probably is.

When you follow this, you'll probably find that your work is in far better shape than you initially thought.

---

On a related note:

>

> I have to present and publish my results anyway if I want to end graduate school and become a phd

>

>

>

Where does this come from? Unless publication is a requirement for graduation (unusual for a master's?), this simply isn't the case. You do not require publications to successfully apply for a PhD. So (unless they're a requirement for graduation) don't stress over publications, treat that possibility as a stretch-goal instead.

---

Some light relief

-----------------

[](http://phdcomics.com/comics.php?f=1972)

[](http://phdcomics.com/comics/archive.php?comicid=1973)

[](http://phdcomics.com/comics/archive.php?comicid=1975)

[](http://phdcomics.com/comics/archive.php?comicid=1976)

[](https://xkcd.com/1954/)

Upvotes: 5 <issue_comment>username_3: It is really difficult to answer this question without knowing your work (and knowing your field to some extent). Maybe there really is a problem with your work, maybe it is just impostor syndrome, which in my personal experience seems to be really common among young scientists. I don't think anyone here is in a position to tell you which one it is.

Personally, I believe that the reason scientists do low-quality work often is that they fail to recognize the problems with their methodology. Having doubts is normal, and I would even go as far as to argue that it might be a good sign because it shows that you have the right attitude, whether your doubts are justified or not.

I agree with the general sentiment of the other answers that it is probably best to ask for feedback from your peers. You have already convinced your supervisor, which is obviously quite important. If you need more positive reinforcement and are worried about particular problems in your work such as the statistical analysis part, consider asking someone to review just that part for you. I have often asked fellow graduate students who I believed to have more expertise than me in a specific field for their opinion on specific parts of my work. Of course, their opinion doesn't carry as much weight as the opinion of an experienced scientist, but it could provide you with some orientation. If several others think your work is fine upon closer inspection, I wouldn't worry about it.

Upvotes: 2 <issue_comment>username_4: I think the beautiful thing about a statistical analysis is that, when done right, it includes the odds that it is incorrect.

The honest thing to do is to include as part of your paper possible confounding factors that may make your conclusions invalid. A good reader is thinking of these anyway, so it only makes you look better to state them in an open way.

You don't have to (and shouldn't) put this in a way that insults your work. But perhaps something like, "A future study where [the data in question] is gathered in [suggested "less dirty" method] would be useful in further understanding this issue."

Frankly, I think your impulse to want a high quality standard for your work is an admirable one.

Upvotes: 3

|

2018/02/26

| 1,223

| 5,175

|

<issue_start>username_0: For the people here who do not yet work entirely electronically, and still use printed papers & old school folders to organise their papers, do you guys have a system for organising these papers?

I have bought a few folders today and have made a few rough distinctions, but I am wondering how more advanced academics organise their papers once they've read hundreds to thousands of them (and also roughly on the same very specialised topic).<issue_comment>username_1: Personally, I am not keen on organizing printed papers. Even though I prefer to read paper documents, I have never been able to devote enough space for proper organization and have resorted to ad hoc printing of those I really want to analyze in detail (knowing that after a few days after reading I will misplace them somewhere) and on-screen reading of those I really only want to skim through.

However, before the introduction of digital technologies, the storage of paper-based documentation was an art. It was perfected by well-known sociologist, <NAME> (indeed, his system of filling cabinet was one of the things that he is famous for). He used system of filling cabinets to store tens of thousands of paper documents: [](https://i.stack.imgur.com/rbCfA.jpg)

As far as I know, he used filling cabbinet-based system for storage of a number of paper fiches, used to organize different ideas: abstracts of books, ideas for papers, etc. I am no aware of him using this method to store full papers, nevertheless you may look into it as an inspiration for your problem solution.

Luhmann's system was subject to a number of studies. Himself, he described the system in the following paper: [Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen](https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-322-87749-9_19). [This](http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/books/b9789004325258s014) seems to be one description of his system in English.

Upvotes: 1 <issue_comment>username_2: Separate the semantic ordering from the physical ordering. It keeps your organization flexible, since you can assign each paper to several topics and projects, and change the assignments as you see fit.

This can be achieved by using a filing cabinet or folders on the one hand, and a bibliographic database (be it electronic or in paper) on the other.

Label each paper with some identifier. I recommend the date or month, but also a running number will do. The label doesn't have to carry any meaning. Collect the papers with a certain range of labels in one folder. For example all papers with labels January to March go in one folder called "Jan-March 2018".

In your database, each entry should also carry the corresponding label under which the paper can be retrieved, in addition to the bibliographic data, and any semantic information such as projects and topic keywords. Use the database, not the physical location, for organizing the papers by substance matter.

How the database itself should be organized is another question. I use folders for projects and keywords for topics. Creating a systematic ontology or adopting an existing ontology (e.g. the Dewey system) seems overkill. Instead, I recommend creating keywords on the fly ("tagging") and combing through the keyword list once in a while. This will be more difficult with a paper-based organization than with an electronic database, of course.

Upvotes: 3 <issue_comment>username_3: I sometimes use printed papers in folders too, because it's nice to be able to peruse them without aid of a computer, especially while in a coffee-shop, etc. Others here suggest using a flexible ordering system, but personnally I find that I use the folder to refresh knowledge of a particular research topic for purposes of writing papers in a specific area. Here is what I put in the folder (in order):

* One folder of papers per for each broad "area" of research (subject to length considerations).

* **Cover and spine:** Cover page and spine page with clear identification of topic, and my contact details on the folder in case I lose it.